Have you ever wondered why we see red light as red? It seems like a simple question, but the answer reveals not only a deep understanding of science but also a fascinating paradox: the particles that make up red light aren’t actually red themselves. This concept isn’t just a quirk of physics - it’s a powerful analogy that applies to many areas of life and science. Just as invisible photons create the visible phenomenon of red light, many systems in our world are composed of parts that don’t resemble the whole they create.

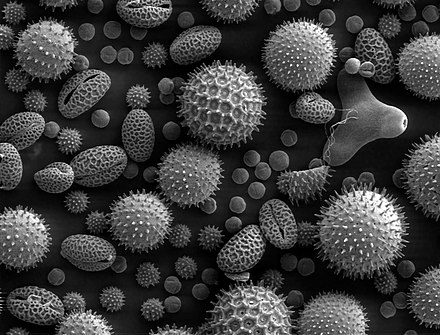

Image of pollen grains taken on a SEM shows the characteristic depth of field of SEM micrographs: view source

Image of pollen grains taken on a SEM shows the characteristic depth of field of SEM micrographs: view source

The rest of

this post tends to set common grounds first as well as attempt to answer the

question: is water wet? using the red light paradox.

Across All Scales

Suppose that you have a digital image on your phone, when you zoom in, you can concetrate your view on a specific area in detail. Just like AppleMaps/GoogleMaps, tiny details on any one view tend to become a composition on several tinnier components. (idea from Eric Weinsten on Steven’s Podcast)

As human beings, we observe objects in nature. Zoom in, we are just a collection of living cells, working together while drifting through space. At the cells level, imagine a single cell to correspond to a human being in contrast to the fact that a cell is a made up of atoms. It becomes clear that an object on Earth can be observed at different scales to contain several components that become tinier every level deeper. Like Fermi’s Paradox, planet Earth is one planet around one star in one galaxy in one universe. The size of a single atom is rationally close to unimaginable on large scales/sizes such as planets or galaxies. It keep me up wondering if everything is large or small.

However, across all scales, most if not all characteristics/properties/aspects of an object fade when focus shifts to a single component that is part of what makes the object. Since we have only two eyes on the human scale level, we are bound to observe objects within the limits of this level. Yes, we can extend our view to smaller/larger scales with special equipments like telescopes or microscopes.

Imagine having an eye whose size corresponds to the moon, how much visual difference in the perception of the stars or planets be? How about eyes at the molecular level?

Now that you can picture the world across different scales, it is time to delve into the red light paradox.

The Science Behind the Analogy

The true nature of light is an interestingly subtle topic in physics. Why red light? Why not green or blue? Well, it’s the same: blue light is not made up of blue particles. To understand this paradox, we need to look into the nature of light itself. Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation that travels in waves. Different colors of light correspond to differenct wavelengths on this electromagnetic spectrum.

A diagram of the electromagnetic spectrum, hightlighting the visible light portion

A diagram of the electromagnetic spectrum, hightlighting the visible light portion

Red light, which we percieve as the color red, has a wavelength of approximately 620-750 nanometers. But here’s where it gets interesting: light is also composed of particles called photons. As discussed in the wave-particle duality theory, these photons are the fundamental units of light. They don’t have any color property themselves. Instead, their energy level determines the wavelength of light they produce.

Our perception of color comes from how our eyes and brain intercept these different wavelengths. When photons with the energy level corresponding to red light hit the photoreceptors in our eyes, our brains interprets this as the color red. The “redness” of red light is more about our perception than an intrinsic property of the photons themselves.

Some Key Examples in Different Fields

This concept of parts not resembling the whole they create extends far beyond light and color. Let’s explore some interesting examples from various fields:

-

Pixels in Digital Images: Just as photons create the illusion of red light, individual pixels create the illusion of a complete image. A single pixel doesn’t contain a miniature version of the picture - it is just a tiny dot of color. It’s only when thousands or millions of these pixels are arranged together that we percieve a coherent image.

A zoomed-in portion of a screen

A zoomed-in portion of a screen -

Atoms in Materials: Consider a gold ring. While the ring is shiny and golden, the idividual atoms that make it up are neither shiny nor gold-colored. The properties we associate with gold emerge from the collective behavior of countless atoms arranged in a specific crystal structure.

-

Notes in Music: A beautiful melody isn’t contained within in any single note. Rather, it emerges from the arrangement and timing of multiple notes. Just as red light requires photons of a specific energy, a melody requires notes played in a specific energy, a melody requires notes played in a specific sequence and rhythm.

-

Genes in Traits: Complex traits in living organismis, like height or intelligence, aren’t determined by single genes. Instead, they result from the intricate interplay of multiple genes and environmental factors. No single gene contains the blueprint for these complex characteristics.

-

Team Members in Sports: In team sports, like soccer or basket ball, victory isn’t acheived by any single player, no matter how talented. Success emerges from the collective effort, strategy, and syngery of the entire team working together - much like how the perception of red light emerges from the collective behavior of photons.

From the above examples, it’s clear that there exists several different areas, cases, or scenarios where the analogy could be applied. In summary;

- Money: Dollar bills aren’t inherently valuable; their worth is assigned.

- Words: Letter in words don’t carry meaning individually; meaning emerges from their combination.

- Neurons: Individual nuerons don’t contain thoughts; it’s thier collective activity.

- Social media likes: A single “like” doesn’t indicate true popularity; it’s the aggregate.

- Ingredients: Individual ingredients don’t represent the final dish’s flavor.

- Data ponts: A single data point doesn’t reveal a trend; it’s the overall pattern.

- Computer code: Single lines of code don’t make a program; it’s their collective function.

- Puzzle pieces: One piece doesn’t show the full picture; it’s how they fit together.

- Chemical elements: Individual elements in a compound don’t exhibit the compound’s properties.

Before we look into the founding question of this post, a clear understanding of the implications of this paradox is a must-have to reach an answer.

The Philosophical Implications

This “Red Light Paradox” challenges our intuitive understanding of the world. It’s a prime example of emergence - the idea that complex systems and patterns arise from relatively simple interactions. This concept stands in contrast to reductionism, which attempts to explainf complex phenomena by breaking them down into simpler parts.

The paradox invites us to adopt a more holistic view of the world. Just as we can’t understand the nature of red light by examining a single photon, we often can’t understand complex systems by studying their components in isolation. This perspective can lead to profound insights in fields ranging from biology to sociology to artificial intelligence.

Is Water Wet?

Well, some many people have approached this in several fascinating ways that fill their conscience. I am not any different and this is my view:

- Water wets other surfaces. A single water molecule doesn’t wet a surface, it’s the

collective effect of many. I argue that water is not wet and that

wettingis as a result of action of water on something solid. Molecules in water are not layered up like bricks so it is wrong to say: A water molecule on top of another implies that the former molecule wets the latter.

Most scientists define wetness as a liquid’s ability to maintain contact with a solid surface, meaning that water itself is not wet, but can make other sensation. But if you define wet as ‘made of liquid or moisture’, as some do, then water and all other liquids can be considered wet. - BBC Science Focus Magazine

Conclusion

From the photons creating red light to the pixels forming digital images, from atoms in materials to notes in music, the world is full of examples where the whole is greater than and different from the sum of its parts. This paradox serves as reminder of the complexity and interconnectedness of our world. Personally, nothing knocks me out like learning about the details of a technology from whole to bits for example how computer graphics boils down to manipulating pixels on a 2d grid. At this point, how might the red light paradox change the way you approach complex problems or systems?

References

- Notes & Queries: The Guardian - Why water is wet?

- Is water wet: BBC Science Focus Magazine - Article